Saving a Theory, Dismissing its Subjects

I’ve been spending the weekend putting together my preliminary research questions and a working bibliography for my graduate program. To my great surprise, I’ve actually been able to read some of the blazingly unempathetic papers about our supposed lack of empathy without spluttering in a fit of moral outrage every five minutes. I call that progress. In fact, I read several articles and found myself able to critique the problems in them rather effortlessly. I credit this development to two things: a) the critical theory I’ve been reading, which helps me to see the larger issues of power and privilege that weave themselves throughout the literature and b) my support network of over 40 people I can call on when the going gets tough.

I’ve been spending the weekend putting together my preliminary research questions and a working bibliography for my graduate program. To my great surprise, I’ve actually been able to read some of the blazingly unempathetic papers about our supposed lack of empathy without spluttering in a fit of moral outrage every five minutes. I call that progress. In fact, I read several articles and found myself able to critique the problems in them rather effortlessly. I credit this development to two things: a) the critical theory I’ve been reading, which helps me to see the larger issues of power and privilege that weave themselves throughout the literature and b) my support network of over 40 people I can call on when the going gets tough.

And then, I read a 2004 article by Uta Frith, and I moved away from my stance of critical detachment toward one of absolute moral outrage.

There I was, enjoying a quiet day at home, reading by the woodstove, minding my own business, and wanting nothing more than to have an enjoyably uneventful time, when I stumbled upon the following piece of remarkably nuanced thinking and stellar prose in Frith’s Emanuel Miller lecture: Confusions and controversies about Asperger syndrome:

“One way to describe the social impairment in Asperger syndrome is as an extreme form of egocentrism with the resulting lack of consideration for others.” (Frith 676)

Don’t you just love when these kinds of prejudicial statements rise up and punch you in the gut? I know I do. It’s just so much fun to read about myself in these terms. You have no idea. And what makes it all the more fun is that the irony of the statement is entirely lost on the writer. She engages in a prejudicial generalization about an entire group of people (otherwise known as a stereotype) and, in the same breath, tells us that we’re the ones with a “lack of consideration for others.”

And here I thought it was autistic people who couldn’t understand irony.

Now, you might not think it could get worse, but that’s because you haven’t read a lot of papers on autism and theory of mind. As it turns out, not only are we egocentric, but we’re unlike those “normal selfish” people who can use egocentrism to their advantage. At least, with them, someone gets something out of it, right? But with us — well, we just can’t help ourselves:

“The self-absorption and disregard of others is not like the strategy that a normal selfish person might deliberately adopt and flexibly use according to what is currently in his or her best interest. Autistic egocentrism, by contrast, appears to be non-deliberate and not determined by what might currently be in the best interest of the individual.” (Frith 676)

In other words, nature has made us selfish. We were just born that way. It’s taken us over and it’s out of our control.

And guess what happens once you peg a whole group of people as being egocentric and selfish? Everything becomes our fault. All the problems in our personal relationships? All our fault! All the problems in our social world? All our fault! You don’t believe me? Read on, my brothers and sisters:

“This egocentrism seems to present a huge difficulty in forming successful long-term interpersonal relationships. Spouses and family members can experience bitter frustration and distress. They are baffled by the fact that there is no mutual sharing of feelings, even when the Asperger individual in question is highly articulate.” (Frith 676)

Yes, you heard it here. We cause people “bitter frustration and distress.” Of course, they do not cause us “bitter frustration and distress.” No. Never. Just doesn’t happen. If we feel “bitter frustration and distress,” it’s all our damned fault for being so, you know, abnormal. If we were only normal, we wouldn’t feel frustrated and distressed. Problem solved!

And, of course, it’s absolutely UNHEARD OF to find a neurotypical person who has difficulty expressing his or her feelings. It just doesn’t happen. Those men I dated and broke up with because I couldn’t get them to articulate a feeling to save their lives? I must have misunderstood where they were coming from. When they were telling me I was hormonal — or refusing to speak altogether — I guess their body language was actually saying, “Yes, honey, I understand and am awash in feeling.”

But of course, I wouldn’t know anything about that, because apparently, I’m just not able to imagine what other people might be thinking. Or so says the author:

“One obstacle seems to be an inability on the part of the person with Asperger syndrome to put themselves into another person’s shoes and to imagine what their own actions look like and feel like from another person’s point of view. Another way to describe the social impairment is as a failure of empathy, involving a poor ability to be in tune with the feelings of other people.” (Frith 676)

I’ve just spent the weekend going through dozens and dozens of articles, and these kinds of statements keep coming up, over and over and over. I can only conclude that the researchers are perseverating on a theme. And I don’t mean for a day, or a week, or a month, but for years and years and years. It’s incredible. You’d think they’d be more flexible and want some change — a broadening of perspective, so to speak — instead of this incessant sameness.

But you know what happens when you try to separate a person from his or her perseverations? It’s not a happy moment. Witness then, the way that the author responds to the fact that autistic people have been writing self-reflective narratives for some time. In a section whose title, “Listening to people with Asperger syndrome,” should really have been “Dismissing people with Asperger syndrome” (or did I miss the intentional irony?), the author makes the following assertions regarding people with Asperger’s who see themselves as having a different experience of the world and a unique perspective on life, rather than being a collection of deficits:

“Researchers and clinicians can agree with this to some extent. However, they may point out that a peculiar lack of insight and an egocentric viewpoint are typical of the syndrome, throwing doubt on at least some of the self-assessments of needs and expectations.” (Frith 681)

In other words, the “experts” have determined that we lack insight and suffer from egocentricism, so whatever we say about our own desires, our own needs, our own experiences, and our own expectations of other people is suspect. Got that? If that’s not a perfect formula for disempowering hundreds of thousands of autistic people, I don’t know what is. And it very neatly closes off the potential for measuring the external validity of the research findings, too.

But, of course, those of us who reflect upon ourselves and others in insightful ways probably don’t have Asperger’s anyway:

“One problem with the autobiographical literature is that the authenticity of the diagnosis is not guaranteed” (Frith 681-682).

Will people ever get tired of the perseverative need to keep saying this? Would it be possible for them to just walk in our shoes and say, “Oh, I see. Now I understand. Thank you for providing a reality check on my lab tests”? Would that really be so terribly difficult?

But the zeal to save a theory from the clutches of reality does not simply extend to talking about our inherent egocentricism and casting doubt on our diagnoses. Oh no. It moves into misinterpretations so extreme that they beggar belief. Take, for example, the following:

“The autobiographies of individuals with Asperger syndrome indicate a high degree of retrospective self-analysis that came with adulthood. This can be seen, for instance, in Gunilla Gerland’s autobiography (1997) and in Clare Sainsbury’s collection of over twenty individuals’ reminiscences of their school years (2000). These works suggest that self-knowledge and sharing of knowledge with others was poor in childhood.” (Frith 683)

So, let’s get this straight: Because we now look back on our childhoods and understand things that weren’t clear before, that in itself is evidence that we lacked self-knowledge and understanding of others as children. Of course, the questions that jump immediately to mind are the following: What self-reflective adult doesn’t look back on childhood and understand things that were opaque before? And what small child understands things the same way as an adult? When non-autistic people look back, reinterpret, and reweave the stories of their lives in narrative form, we laud them for being mature, creative, and insightful. But when autistic people look back, reinterpret, and reweave the stories of our lives in narrative form, we’re told it’s evidence that we lacked theory of mind in childhood.

Not too much confirmation bias there.

But the theory must be saved. Oh, yes. And its subjects must be dismissed.

Source

Frith, Uta. “Emanuel Miller lecture: Confusions and controversies about Asperger syndrome.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 45, no. 4 (May 2004): 672-686. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00262.x.

Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg blogs at Journeys with Autism, and presides at Autism and Empathy.

Saving a Theory, Dismissing its Subjects appears here by permission.

The most recent installment in Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg’s published memoirs is Blazing My Trail.

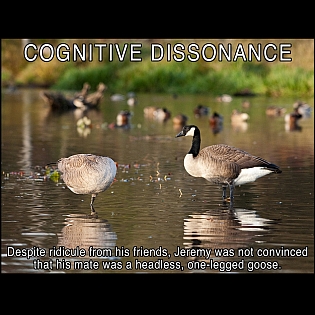

[image via Flickr/Creative Commons]

Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg on 01/3/12 in Autism, featured | 1 Comment | Read More

Comments (1)

“One way to describe the social impairment in Asperger syndrome is as an extreme form of egocentrism with the resulting lack of consideration for others.” (Frith 676)

Yeah, that’s why I, a twice-diagnosed confirmed Aspie, devote myself to social justice, anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-ableist, gay rights, and environmental justice struggles, why I jump at opportunities to volunteer, why I spend hours helping my friends both NT and Aspie through their emotional and social problems, and why I keep giving to every beggar, charity, and cause that asks me even when I’m struggling to buy textbooks- because I don’t care about other people.